Let's have Christmas in Hanoi, Vietnam!

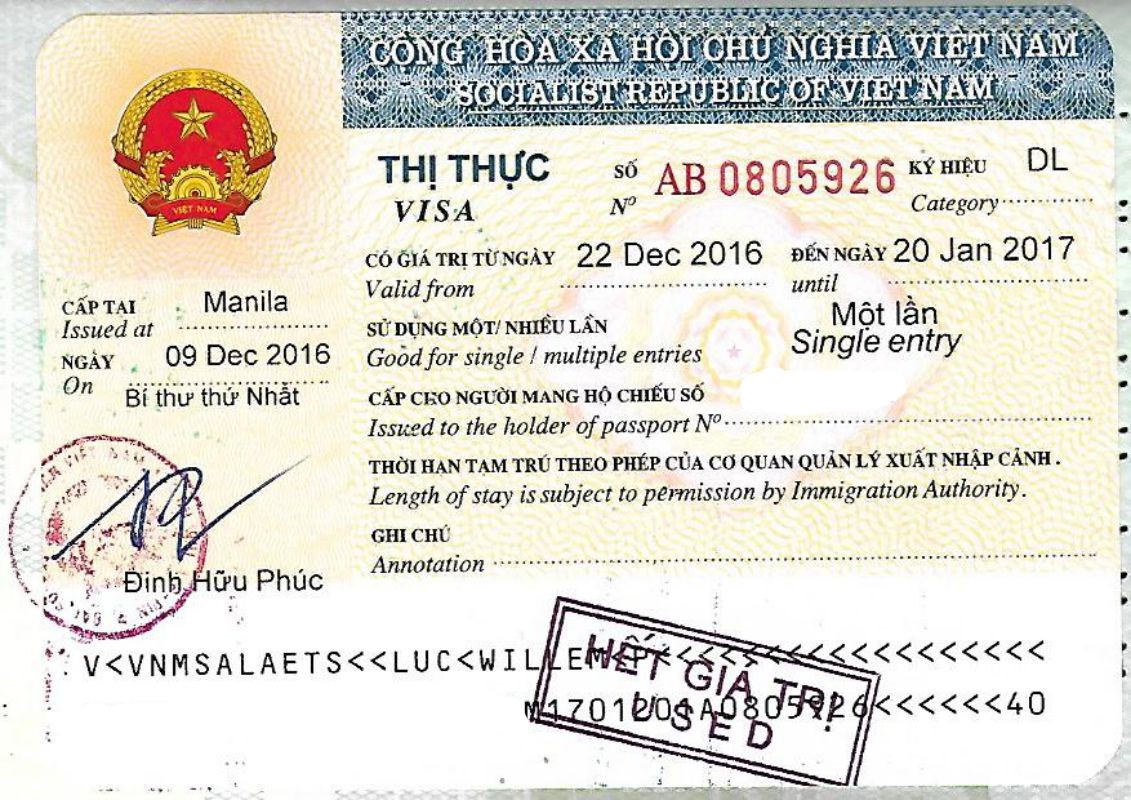

That was the idea late 2016, seeing a promo on Cebu Pacific. But after exploring the possibility we discovered Luc needs a tourist visa to visit Vietnam. Filipinos do not need a tourist visa if the duration is less than 21 days. The process to get a tourist visa is very simple; can do it online or go to the Embassy and request a tourist visa. To avoid surprises we got the visa from the Embassy of Vietnam in Manila.

The flight with Cebu Pacific only cost PHP 8,857.23 per person.

The flight with Cebu Pacific only cost PHP 8,857.23 per person.

Cheap flights are usually taking off late in the evening or early in the morning, so we arrived just after midnight in Hanoi airport. There is a one hour difference with Manila. No problem at immigration. A pick up was arranged by the hotel.

The airport is about 30KM from the city and around 45 mins to arrive at the hotel

Impressive hotel Hanoi is a small building in a very dense neighborhood. But nevertheless charming and super friendly. There are less than 10 rooms and the clientele was mostly westerners working at NGOs or UN offices according to the staff.

Western penetration of Vietnam

In 1516 Portuguese adventurers arriving by sea inaugurated the era of Western penetration of Vietnam. They were followed in 1527 by Dominican missionaries, and eight years later a Portuguese port and trading centre were established at Faifo (modern Hoi An), south of present-day Da Nang. More Portuguese missionaries arrived later in the 16th century, and they were followed by other Europeans. The best-known of these was the French Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes, who completed a transcription of the Vietnamese language into Roman script that later was adopted by modern Vietnamese as their official writing system, Quoc-ngu (“national language”).

By the end of the 17th century, however, the two rival Vietnamese domains (under the Nguyen family in the south, and the Trinh family in the north) had lost interest in maintaining relations with European countries; the only window left open to the West was at Faifo, where the Portuguese retained a trading mission. For decades the French had tried without success to retain some influence in the area. Only at the end of the 18th century was a missionary named Pigneau de Béhaine able to restore a French presence by assisting Nguyen Anh in wresting control of Dai Viet from the Tay Sons.

Upon becoming emperor, however, Nguyen Anh (now Gia Long) did not favour Christianity. Under his strongly anti-Western successor, Minh Mang (ruled 1820–41), all French advisers were dismissed, while seven French missionaries and an unknown number of Vietnamese Christians were executed. After 1840 French Roman Catholic interests openly demanded military intervention to prevent the persecution of missionaries. In 1847 the French took reprisals against Vietnam for expelling additional missionaries, but 10 years passed before Paris prepared a military expedition against Vietnam.The conquest of Vietnam by France

The decision to invade Vietnam was made by Napoleon III in July 1857. It was the result not only of missionary propaganda but also, after 1850, of the upsurge of French capitalism, which generated the need for overseas markets and the desire for a larger French share of the Asian territories conquered by the West. The naval commander in East Asia, Rigault de Genouilly, long an advocate of French military action against Vietnam, was ordered to attack the harbour and city of Tourane (Da Nang) and to turn it into a French military base. Genouilly arrived at Tourane in August 1858 with 14 vessels and 2,500 men; the French stormed the harbour defenses on September 1 and occupied the town a day later. Genouilly soon recognized, however, that he could make no further progress around Tourane and decided to attack Saigon. Leaving a small garrison behind to hold Tourane, he sailed southward in February 1859 and seized Saigon two weeks later.

Vietnamese resistance prevented the French from advancing beyond Saigon, and it took French troops, under new command, until 1861 to occupy the three adjacent provinces. The Vietnamese, unable to mount effective resistance to the invaders and their advanced weapons, concluded a peace treaty in June 1862, which ceded the conquered territories to France. Five years later additional territories in the south were placed under French rule. The entire colony was named Cochinchina.

It had taken the French slightly more than eight years to make themselves masters of Cochinchina (a protectorate already had been imposed on Cambodia in 1863). It took them 16 more years to extend their control over the rest of the country. They made a first attempt to enter the Red River delta in 1873, after a French naval officer and explorer named Francis Garnier had shown, in a hazardous expedition, that the Mekong River could not serve as a trade route into southwestern China. Garnier had some support from the French governor of Cochinchina, but when he was killed in a battle with Chinese pirates near Hanoi, the attempt to conquer the north collapsed.

Within a decade, France had returned to the challenge. In April 1882, with the blessing of Paris, the administration at Saigon sent a force of 250 men to Hanoi under Capt. Henri Rivière. When Rivière was killed in a skirmish, Paris moved to impose its rule by force over the entire Red River delta. In August 1883 the Vietnamese court signed a treaty that turned northern Vietnam (named Tonkin by the French) and central Vietnam (named Annam, based on an early Chinese name for the region) into French protectorates. Ten years later the French annexed Laos and added it to the so-called Indochinese Union, which the French created in 1887. The union consisted of the colony of Cochinchina and the four protectorates of Annam, Tonkin, Cambodia, and Laos.

Colonial Vietnam

French administration

The French now moved to impose a Western-style administration on their colonial territories and to open them to economic exploitation. Under Gov.-Gen. Paul Doumer, who arrived in 1897, French rule was imposed directly at all levels of administration, leaving the Vietnamese bureaucracy without any real power. Even Vietnamese emperors were deposed at will and replaced by others willing to serve the French. All important positions within the bureaucracy were staffed with officials imported from France; even in the 1930s, after several periods of reforms and concessions to local nationalist sentiment, Vietnamese officials were employed only in minor positions and at very low salaries, and the country was still administered along the lines laid down by Doumer.

Doumer’s economic and social policies also determined, for the entire period of French rule, the development of French Indochina, as the colony became known in the 20th century. The railroads, highways, harbours, bridges, canals, and other public works built by the French were almost all started under Doumer, whose aim was a rapid and systematic exploitation of Indochina’s potential wealth for the benefit of France; Vietnam was to become a source of raw materials and a market for tariff-protected goods produced by French industries. The exploitation of natural resources for direct export was the chief purpose of all French investments, with rice, coal, rare minerals, and later also rubber as the main products. Doumer and his successors up to the eve of World War II were not interested in promoting industry there, the development of which was limited to the production of goods for immediate local consumption. Among these enterprises—located chiefly in Saigon, Hanoi, and Haiphong (the outport for Hanoi)—were breweries, distilleries, small sugar refineries, rice and paper mills, and glass and cement factories. The greatest industrial establishment was a textile factory at Nam Dinh, which employed more than 5,000 workers. The total number of workers employed by all industries and mines in Vietnam was some 100,000 in 1930. Because the aim of all investments was not the systematic economic development of the colony but the attainment of immediate high returns for investors, only a small fraction of the profits was reinvested.

Effects of French colonial rule

Whatever economic progress Vietnam made under the French after 1900 benefited only the French and the small class of wealthy Vietnamese created by the colonial regime. The masses of the Vietnamese people were deprived of such benefits by the social policies inaugurated by Doumer and maintained even by his more liberal successors, such as Paul Beau (1902–07), Albert Sarraut (1911–14 and 1917–19), and Alexandre Varenne (1925–28). Through the construction of irrigation works, chiefly in the Mekong delta, the area of land devoted to rice cultivation quadrupled between 1880 and 1930. During the same period, however, the individual peasant’s rice consumption decreased without the substitution of other foods. The new lands were not distributed among the landless and the peasants but were sold to the highest bidder or given away at nominal prices to Vietnamese collaborators and French speculators. These policies created a new class of Vietnamese landlords and a class of landless tenants who worked the fields of the landlords for rents of up to 60 percent of the crop, which was sold by the landlords at the Saigon export market. The mounting export figures for rice resulted not only from the increase in cultivable land but also from the growing exploitation of the peasantry.

The peasants who owned their land were rarely better off than the landless tenants. The peasants’ share of the price of rice sold at the Saigon export market was less than 25 percent. Peasants continually lost their land to the large owners because they were unable to repay loans given them by the landlords and other moneylenders at exorbitant interest rates. As a result, the large landowners of Cochinchina (less than 3 percent of the total number of landowners) owned 45 percent of the land, while the small peasants (who accounted for about 70 percent of the owners) owned only about 15 percent of the land. The number of landless families in Vietnam before World War II was estimated at half of the population.

The peasants’ share of the crop—after the landlords, the moneylenders, and the middlemen (mostly Chinese) between producer and exporter had taken their share—was still more drastically reduced by the direct and indirect taxes the French had imposed to finance their ambitious program of public works. Other ways of making the Vietnamese pay for the projects undertaken for the benefit of the French were the recruitment of forced labour for public works and the absence of any protection against exploitation in the mines and rubber plantations, although the scandalous working conditions, the low salaries, and the lack of medical care were frequently attacked in the French Chamber of Deputies in Paris. The mild social legislation decreed in the late 1920s was never adequately enforced.

Apologists for the colonial regime claimed that French rule led to vast improvements in medical care, education, transport, and communications. The statistics kept by the French, however, appear to cast doubt on such assertions. In 1939, for example, no more than 15 percent of all school-age children received any kind of schooling, and about 80 percent of the population was illiterate, in contrast to precolonial times when the majority of the people possessed some degree of literacy. With its more than 20 million inhabitants in 1939, Vietnam had but one university, with fewer than 700 students. Only a small number of Vietnamese children were admitted to the lycées (secondary schools) for the children of the French. Medical care was well organized for the French in the cities, but in 1939 there were only 2 physicians for every 100,000 Vietnamese, compared with 76 per 100,000 in Japan and 25 per 100,000 in the Philippines.

Two other aspects of French colonial policy are significant when considering the attitude of the Vietnamese people, especially their educated minority, toward the colonial regime: one was the absence of any kind of civil liberties for the native population, and the other was the exclusion of the Vietnamese from the modern sector of the economy, especially industry and trade. Not only were rubber plantations, mines, and industrial enterprises in foreign hands—French, where the business was substantial, and Chinese at the lower levels—but all other business was as well, from local trade to the great export-import houses. The social consequence of this policy was that, apart from the landlords, no property-owning indigenous middle class developed in colonial Vietnam. Thus, capitalism appeared to the Vietnamese to be a part of foreign rule; this view, together with the lack of any Vietnamese participation in government, profoundly influenced the nature and orientation of the national resistance movements.

Comments powered by CComment