Leuven, the university city of flanders, with a rich history even in recent years. Let's hav a look in winter. First, put some gasoline in the car...

Parked the car at Leuven railway station and walk from there to the center.

Gaz up the car. Selfservice

Gaz up the car. Selfservice Get the receipt dear...

Get the receipt dear... Hotel Royal, a long-standing building opposite Leuven train station, facing Martelarenplain

Hotel Royal, a long-standing building opposite Leuven train station, facing Martelarenplain Accross the road, Another long-standing building, Hotel Industrie

Accross the road, Another long-standing building, Hotel Industrie Free bicycle parking lot

Free bicycle parking lot Fonske, Quirky monument honoring the city's educational heritage, located in a striking historic square. In the background, City Hall

Fonske, Quirky monument honoring the city's educational heritage, located in a striking historic square. In the background, City Hall Magnificent Leuven City Hall today

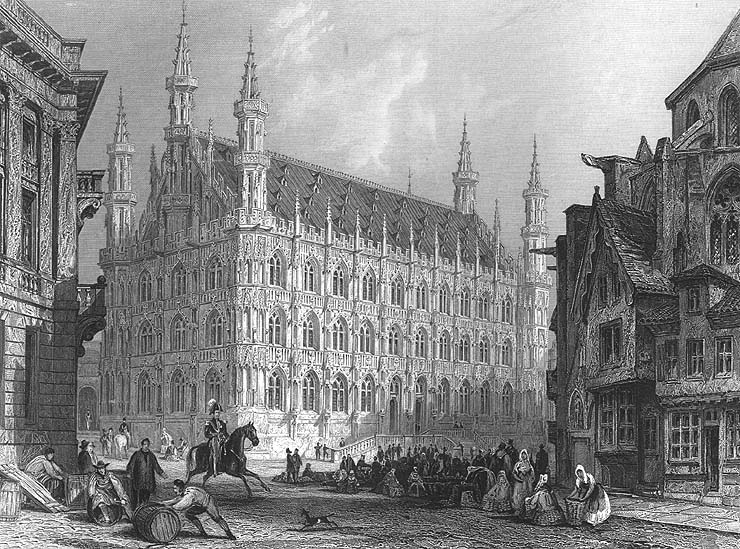

Magnificent Leuven City Hall today Magnificent Leuven City Hall in 1865

Magnificent Leuven City Hall in 1865History Town Hall

Along with her big sister, who dominates Brussels’ Grand Place, Leuven’s Town Hall is a shining example of the wow factor that Brabantine Gothic architecture is aimed to inspire. Even with a ‘hall of fame’ façade boasting 236 statuettes as its most striking feature, the building maintains a certain elegance thanks to its slender frame. The historic Town Hall in the middle of the student city’s main square hasn’t always been quite as eye-catching as it is today. Less than two centuries ago it actually looked a little barren, standing across from the hulking St. Peter’s Church with no biblical or saintly statues to speak of. Its lack of bravado in the sculpture department even prompted Victor Hugo to comment: ‘a civil or church building with empty alcoves is like a book with empty pages.’

The initiative to embellish the exterior with local heroes, scientists and saints only came in 1847 – over 400 years after the Town Hall was constructed. With Belgium fresh off its revolution, the government of the newborn nation felt an intense need to re-establish the tiny country’s rich cultural heritage and nothing says ‘history of excellence’ like planting a pantheon on your cities’ ultimate political symbols. While the Leuvenaars themselves weren’t initially too keen on the idea of flashy and expensive additions to their City Hall, the go-ahead was given by King Leopold I and a competition was set up to select the sculptors who’d get the honor of transforming the building’s edifice into the iconic display of statues wall we see today.

Since the artists’ creations carry no inscriptions or name tags, however, there’s no easy way of telling who’s who in the army of statuettes. Yet on the ground floor you can be sure to find prominent Leuvenaars, often scholars and scientists – the city remains home to Belgium’s very first university, after all. The first floor is reserved for the patron saints of Leuven’s parishes and symbolic figures, while the aristocracy, including the Dukes of Brabant and Counts of Leuven, looks down on the populace from up top.

Taken by the façade’s immediate splendor and the incredibly detailed features of its stone men and women, many passers-by forget that the part of Town Hall boasting all these ornaments is merely one wing of a much larger complex. The fact is that the mayor’s seat occupies the entire block that stretches between the city’s main square and the gourmet alley Muntstraat. The flamboyant edifice also hides a courtyard known as ‘het Vrijthof’ and another building that’s older still.

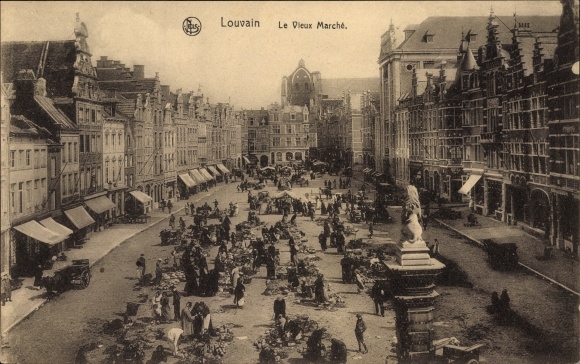

The Old Market is quiet in Winter time. The reference of the longest bar in the world certainly holds up in the warmer months. This location is one of the oldest and most historic in all of Leuven. The square has existed in its present form since the 14th Century, when the Old University of Leuven was established. Most of the square's buildings are built in the Gothic style, of which the town hall is a prime example.

Other buildings on the Grote Markt are the Church of St. Peter and several guild houses. As throughout Leuven, there are also many pubs, taverns, and eateries on the Grote Markt. There is a significant contrast between the more formal and traditional style establishments on the Grote Markt and the more trendy, youth-oriented and student entertainment spots on the nearby Oude Markt.

The old Market or "Oude Markt"

The old Market or "Oude Markt" Old market. At the end: the Holy Trinity College or 'Heilige-Drievuldigheidscollege'

Old market. At the end: the Holy Trinity College or 'Heilige-Drievuldigheidscollege' Old market around 1900

Old market around 1900 Old Market in the past

Old Market in the pastA quick visit to the St Peters Church or "St Pieterskerk". the church has a cruciform floor plan and a low bell tower that has never been completed.

St Pieter's church west facade. Tower was never finish

St Pieter's church west facade. Tower was never finish St Pieter's church exterior. Choir and ridge

St Pieter's church exterior. Choir and ridge Sacrament Tower

Sacrament Tower Baroque pulpit

Baroque pulpit Priest Choir

Priest Choir Detailed woodwork on the pulpit bottom

Detailed woodwork on the pulpit bottom Tombe Henry I

Tombe Henry I The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, painted by Dirk Bouts

The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, painted by Dirk Bouts Descent from the cross painted by Rogier van der Weyden.

Descent from the cross painted by Rogier van der Weyden. Interior of the St. Peter's Church, Leuven by Wolfgang de Smet, 1667

Interior of the St. Peter's Church, Leuven by Wolfgang de Smet, 1667History

The first church on the site, made of wood and presumably founded in 986, burned down in 1176. It was replaced by a Romanesque church, made of stone, featuring a West End flanked by two round towers like at Our Lady's Basilica in Maastricht. Of the Romanesque building only part of the crypt remains, underneath the chancel of the actual church.

Construction of the present Gothic edifice, significantly larger than its predecessor, was begun approximately in 1425, and was continued for more than half a century in a remarkably uniform style, replacing the older church progressively from east (chancel) to west. Its construction period overlapped with that of the Town Hall across the Markt, and in the earlier decades of construction shared the same succession of architects as its civic neighbor: Sulpitius van Vorst to start with, followed by Jan II Keldermans and later on Matheus de Layens. In 1497 the building was practically complete, although modifications, especially at the West End, continued.Towers

In 1458, a fire struck the old Romanesque towers that still flanked the West End of the uncompleted building. The first arrangements for a new tower complex followed quickly, but were never realized. Then, in 1505, Joost Matsys (brother of painter Quentin Matsys) forged an ambitious plan to erect three colossal towers of freestone surmounted by openwork spires, which would have had a grand effect, as the central spire would rise up to about 170 m,[2] making it the world's tallest structure at the time. Insufficient ground stability and funds proved this plan impracticable, as the central tower reached less than a third of its intended height before the project was abandoned in 1541. After the height was further reduced by partial collapses from 1570 to 1604, the main tower now rises barely above the church roof; at its sides are mere stubs. The architect had, however, made a maquette of the original design, which is preserved in the southern transept.

Despite their incomplete status, the towers are mentioned on the UNESCO World Heritage List, as part of the Belfries of Belgium and France.War and after war

The church suffered severe damage in both World Wars. In 1914 a fire caused the collapse of the roof and in 1944 a bomb destroyed part of the northern side.

The reconstructed roof is surmounted at the crossing by a flèche, which, unlike the 18th-century cupola that preceded it, blends stylistically with the rest of the church.

A very late (1998) addition is the jacquemart, or golden automaton, which periodically rings a bell near the clock on the gable of the southern transept, above the main southern entrance door.Artworks and relics

Despite the devastation during the World Wars, the church remains rich in works of art. The chancel and ambulatory were turned into a museum in 1998, where visitors can view a collection of sculptures, paintings and metalwork.

The church has two paintings by the great Flemish painter Dirk Bouts on display, the Last Supper (1464-1468) and The Martyrdom of St Erasmus (1465). The Nazis seized The Last Supper in 1942. Panels from the painting had been sold legitimately to German museums in the 1800s, and Germany was forced to return all the panels as part of the required reparations of the Versailles Treaty after World War I.

Next, we stroll over the weekly market in the Brusselstraat, a pedestrianised shopping street

Flower & plants

Flower & plants White asparagus is simply green asparagus that has never seen the light of day when growing.

White asparagus is simply green asparagus that has never seen the light of day when growing.  Flavoured dried sausage and cheeses

Flavoured dried sausage and cheeses Let's go NUTS

Let's go NUTS Fruits galore

Fruits galore Brazilian Mangoes

Brazilian Mangoes Classic cheeses

Classic cheeses How big you want it

How big you want it Coffee selection

Coffee selection And don't forget the bakkery

And don't forget the bakkeryWalking in the direction of the station, passing the Ladeuzen square or "Ladeuzenplein". With the large library building flanking the aquare. This building has a controversional history...

University Leuven

University Leuven Hogeschoolplein

Hogeschoolplein Walking the back alley

Walking the back alley Walking the back alley

Walking the back alley The University Library fronting Ladeuzenplein

The University Library fronting Ladeuzenplein he University Library tower

he University Library tower he University Library at dusk

he University Library at duskInside the Belgian Library That Tore Itself Apart

In the 1960s, a conflict between Dutch-speaking and French-speaking students divided a historic collection.

Founded in 1425, the institution—known in French as the Université catholique de Louvain and in Dutch as the Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven—was no longer viable despite its rich legacy, and its national symbolic value. As in many places in the country, French speakers, known as Walloons, had long enjoyed special status at the institution, controlling its administration despite Leuven’s location in the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders. Fed up, the Flemish students demanded that the university rectify historic inequities and finally prioritize its Dutch-speaking majority.

The institution had torn apart at its factional seams, and nothing less than a split down the middle would suffice. This division would ultimately require the construction of a new town, Louvain-la-Neuve (literally “New Leuven” in French) and a new campus just across the border, only about 40 minutes’ drive away. But dividing the library’s collection—splitting an expression of a unified culture, a shared history—may have been harder than building a new city.

And so, in the 1970s, as Wallonia’s new Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain) was under construction, Leuven’s library was a house divided. While the Walloons waited for their new library to be completed, this historic building near the center of Belgium—about 18 miles from the border separating Flanders and Wallonia—now temporarily housed two distinct libraries serving two distinct institutions, one for each linguistic community. Students, faculty, and staff were “working in the same place, but not working together,” says Charles-Henri Nyns, now UCLouvain’s Chief Librarian, and a student in Leuven during the 1970s, when the split was underway. Staff members were instructed, he says, to assist students in one language only and not the other—to not answer students who approached them in the wrong language.

All that determined which language you used was whether fortune had named you a Fleming or a Walloon; accordingly, books were split between the two institutions based not on their language, or their subject matter, but largely on their own labels—their shelfmarks.

How else to split a collection that held more than just books, but the weight of the past itself? Some of that history was proud: Erasmus had found an intellectual home in the city during the 16th century, and the library held his letters. The building catalogued the Low Countries’ contributions to the arts and sciences, documenting intellectual movements, such as Dutch Humanism and Jansenism. In a country known for its lack of a cohesive national identity, the library seemed as close to a symbol of unity—of Belgian-ness—as could be found.

Its tragic, brutal sacking in the First World War only reaffirmed that symbolism. On August 25, 1914, the German military set the library ablaze as part of its collective punishment of Leuven in retaliation for an alleged sniper attack. According to research by Mark Derez, archivist for the Flemish institution (KU Leuven), more than 2,000 houses burned down, 248 people died, and there “rained fragments of charred paper as far as the surrounding countryside.”

The town became a convenient piece of propaganda for the forces unified against Germany. In England, Derez writes, some ships and even baby girls born in 1914 were named after the town, as “Louvain! shall be our Battle Cry” became the name of a military march. The burnt library in particular was so poignant, writes Derez, because no one could have justified its military value. Its image helped recast the war from “a political-military conflict” into “a clash of civilizations,” in which one side would destroy cultural relics in fits of wanton, nihilistic aggression.

Derez relays an anecdote, possibly apocryphal, in which someone whose family’s home burned down during the German attack tried to describe the carnage to an American diplomat. He got through his family’s story but kept stumbling over the word “bibliothèque,” before bursting into tears. Even if the story is not actually true, its telling illustrates Derez’s key observation. “Attacks on cultural goods,” he writes, “continue to burn in people’s minds and to precipitate into the collective memory. The symbolic order ultimately outweighs individual tragedy.”

Not everyone, however, was ready to rally around the library to help Belgium heal the wounds of the war. Some Flemish students who had fought for Belgium on the battlefield boycotted the newly built library’s dedication ceremony in 1928, as the Institut de France’s involvement in the project signaled to them a pro-Francophone bias. “French was seen as a language of social pressure and a language of arrogance,” says Derez in an interview, and not even the Germans’ flames could erase that impression. (The German military attacked the library yet again in 1940, during World War II.)

When the episcopate had taken control of the university in 1834, following the establishment of the Kingdom of Belgium, instruction and administration were made almost exclusively French, despite the university’s location in Dutch-speaking Flanders. (The one exception was a course in Flemish literature.) Feeling as though they were invisible, the Flemings “perceived their French-speaking colleagues as aristocratic, snobbish, patronizing, and condescending bourgeois, who remained convinced of the superiority of the French language and therefore refused to learn Dutch,” writes Louis Vos, an historian at KU Leuven. The institution did not begin to add more Dutch courses until 1911, following decades of Flemish nationalist activism.

By 1936, the university had expanded to include a fully Dutch track for students, but the expansion only segregated the two language groups—rendering them separate, and decidedly unequal. When Vos was attending the university in the 1960s, he says the same lecture hall would host the same course two periods in a row: one session for each language. Students would ignore each other completely as they shuffled in and out. As the split was underway during the 1970s, says Nyns, the Walloon community was “like a ghetto”; he was able to make some Flemish friends, but only through proactive effort. Vos, meanwhile, says he never once conversed directly with a French speaker during his time as a student in Leuven.

“The idea that Belgium is a bilingual state is not completely correct,” Vos says. The situation is closer to one of “self-chosen apartheid” based on “real hostility”—and carried out, of course, unequally. He recalls Francophone students getting to use nice laboratories while Flemish students were relegated to the basement, studying the sciences on a smaller budget despite making up more of the student body.

And so, the Flemish protests persisted throughout the 1960s (some of them violently). The students sang “We Shall Overcome” and chanted “Walen buiten!”—“Walloons out!”—until it ultimately came to pass that each group would have to be served by its own distinct institution. Though much of the collection—which had twice been violently attacked—was necessarily new, the battle for the library’s holdings was still the sticking point; the library still embodied a long and vibrant history. In addition to the letters of Erasmus, the collection boasted writings by Thomas More, as well as the oldest manuscript written in the Hungarian language—part of Germany’s reparations for World War I, as mandated by the Treaty of Versailles. Derez recalls a colleague hiding a rare, 15th-century prayer book (shelfmark A12) in his own bedroom in order to hide it from the Walloons, so that they might not take it with them to their new town.*

The administrators eventually settled on some arbitrary ground rules, which seemed fairest under the circumstances. If a work’s donor could be contacted, the donor could choose where it would go—and if there was more than one version of the same work, each institution would be guaranteed at least one copy. But the majority of works were just divided by shelfmark: Odds stayed in Leuven, evens left for Louvain-la-Neuve. It was an oddly prosaic solution to a fundamentally emotional conflict. Along with Walloon students and faculty—who, Nyns remembers, “lost their homes”—the books moved across the border, populating this new prop college town that was then, according to Vos, nothing but open fields.

Today, the two institutions enjoy a peaceful relationship, occasionally convening for ceremonies, and routinely collaborating on research. Law students, adds Nyns, often spend six months at the other school, as many Belgian lawyers are expected to be bilingual. But it’s a cold peace. The current students on either side of the border rarely speak one another’s language, and Walloons and Flemings often have to communicate with each other in English, says Derez. (He adds that Belgium’s German-speaking minority—less than one percent of the population—are known as “the last Belgians,” caught between the country’s two distinct factions.) He wonders if the partnership between the two institutions will evaporate within the next few generations, when there will be no one left to link the two groups.

Perhaps then—in the absence of a unified Belgium—the split will seem even more, as Derez insists, like “a typical Belgian solution” after all.

Comments powered by CComment