Let go back in time by visiting Brugge, the medieval city of Flanders. Brugge’s intricate network of canals has led many to describe the city as the Venice of the North. A short train ride takes us there.

Arriving at Brugge station.

Arriving at Brugge station. Brugge station square

Brugge station square Walking to the center

Walking to the center Antique facades while walking to the center

Antique facades while walking to the center Brugge canals

Brugge canals Brugge canal boat rides, kinda crowded boats

Brugge canal boat rides, kinda crowded boats Entrance Church of Our Lady or Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk

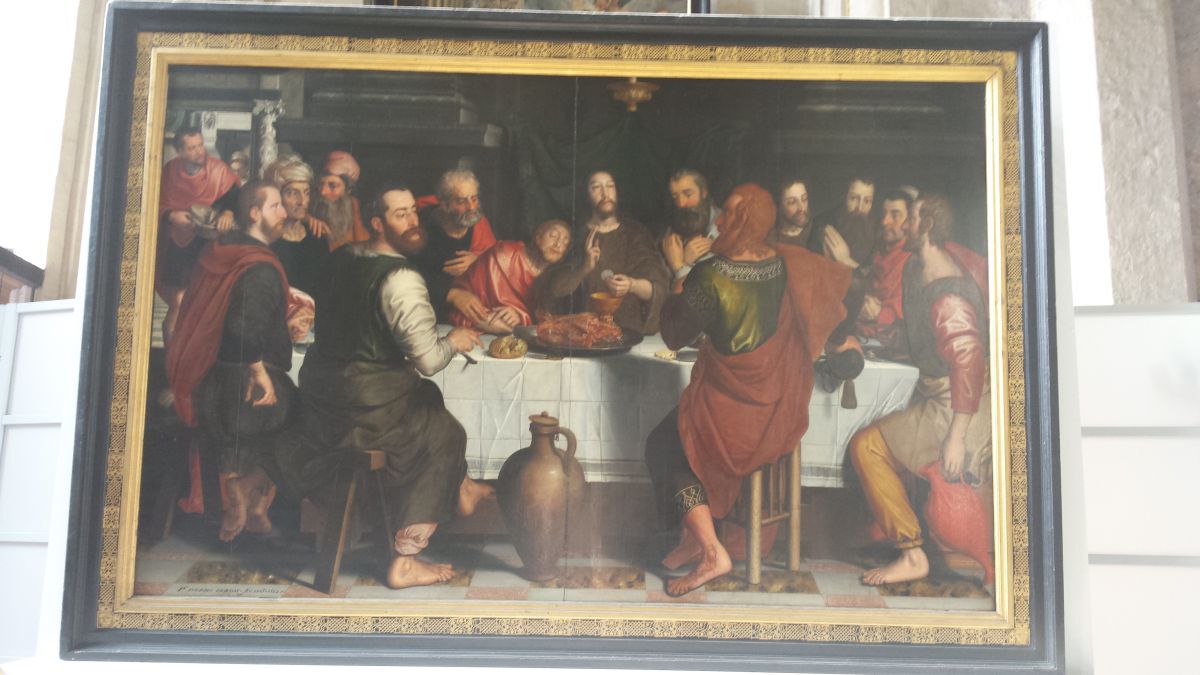

Entrance Church of Our Lady or Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk  The Last Supper, painter by Pieter Pourbus in 1562

The Last Supper, painter by Pieter Pourbus in 1562 Church interior

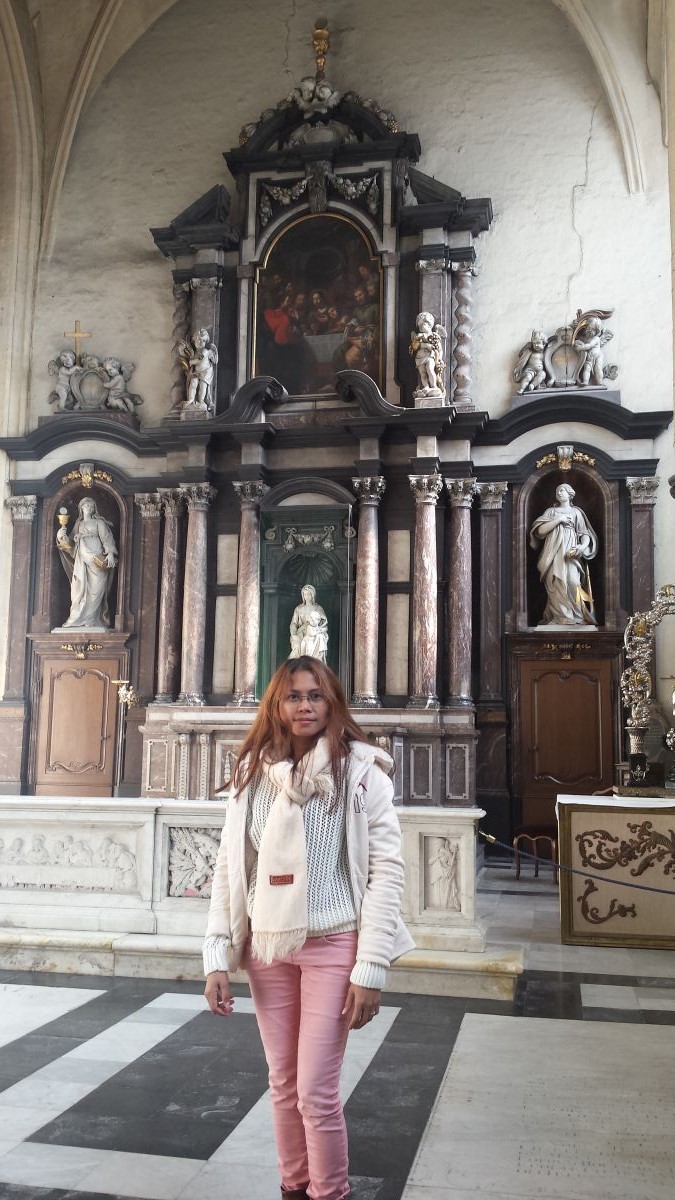

Church interior Jas in front of "The Madonna"

Jas in front of "The Madonna" Our Lady of seven sorrows Painting by Adriaen Isenbrandt

Our Lady of seven sorrows Painting by Adriaen Isenbrandt Michelangelo's Madonna-and-child

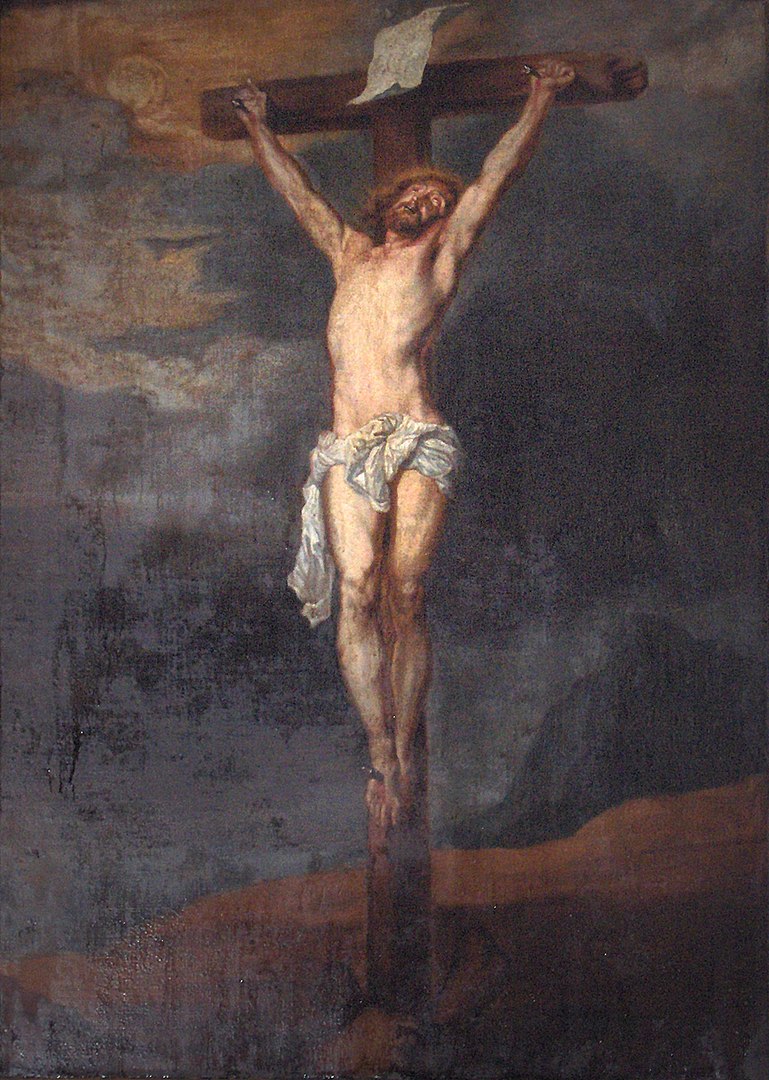

Michelangelo's Madonna-and-child Crucifixion by Anthony van Dyck

Crucifixion by Anthony van Dyck The altarpiece of the large chapel in the southern aisle

The altarpiece of the large chapel in the southern aisle Church of Our Lady construction history

The first church in this place, a Carolingian chapel, dates from circa 875. In the archives of the church, the foundation is dated 741 and attributed to Boniface , but this claim is questionable, since the oldest patronymic dates back to his companion Hilarius. . The chapel depended on the Sint-Maartenskerk in Sijsele , which in turn owned the Dom van Utrecht . In 1116 the chapel separated from Sijsele and became the main church of an independent parish . Presumably, therefore, the building was rebuilt and expanded under Charles the Good .

The construction of the current church started from about 1230. The oldest part, the central aisle , was built in Tournai stone , in the typical Scheldt Gothic . The influence of the Scheldt Gothic, with the two typical stair towers and the use of blue stone, can also be recognized on the front and west facades. The choir section and the apse , built between 1270 and 1280, radiate the classic French Gothic , but completely in brick. The northern beech was built in 1370 and the southern beech in 1450. Around 1465, the Paradise Portal was built in Brabant Gothic .

The tower of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk is the tallest building in the city of Bruges. The first tower collapsed in 1163 and was rebuilt between about 1270 and 1340; the spire was only added in the 15th century and rebuilt in the 19th century . The use of brick is typical of the coastal Gothic. The church has five naves. In the middle of the central aisle, the three-part hall divides the church into two parts: the high choir and the nave. The apostle statues are from the 17th century .Tombs and choir

The church is known, among other things, because Mary of Burgundy is buried there. Her remains were identified during archaeological research in 1979. Her father, Karel de Stoute , only contains the tomb here. His remains were taken from France to Bruges by Emperor Charles V , a grandson of Mary. He was probably buried in the now-disappeared Saint Donatian Cathedral on the Burg. His body was never recovered. The tombs are located in the high choir of the church.

Above the high altar is a triptych by the court painter of Margaret of Austria , Bernard van Orley . It is a passion story with the crucifixion in the middle. At the foot of the altar, under the tombs, three graves are richly painted.

The lead casket in one of the graves (visibly arranged) contains the bones of Mary, who died in Bruges in 1482. An inscription indicates that the heart of her son Philip the Fair , father of Charles V, was stored in a separate lead box.

The tomb of Mary and also the oldest, was designed by Jan Borman . Both princes are depicted in a lying position and folded hands, according to medieval custom. With opened eyes they are in sight of eternal life. At their feet, the lion and dog act as symbols of masculine strength and feminine fidelity.

Mary of Burgundy's face is gossamer, modeled after the death mask. Her crown decorated with precious stones, her hands and her lavishly wavy cloak are miniature works of art. The funerary monument is still completely Gothic in concept and spirit.

The tomb of Charles the Bold is half a century younger. The effect is partly Gothic, partly Renaissance . The lines are much tighter, but the armor is artfully and detailed. Both black sarcophagi have plaques on the front and on the side walls you see the enamelled family shields of the ancestors. Photos of the tombs can be found in the articles devoted to Mary of Burgundy and Charles the Bold.

Thirty coats of arms of knights of the Golden Fleece hang above the choir stalls . The first shield on the left is that of Charles the Bold, just opposite that of his brother-in-law Edward IV of England . The coats of arms recall the chapter of the Order of the Golden Fleece that was held in this church in 1468.Michelangelo - Mary with Child

The world-famous work by Michelangelo , Madonna and Child , intended for the Piccolomial altar of the Siena Cathedral , is one of the most important works of art preserved in the Church of Our Lady. It was purchased in Italy by the Bruges merchant Jan van Moeskroen (Giovanni di Moscerone) and donated to the church in 1514. The donor's family tomb is at the foot of the altar, in front of the statue.

The statue was removed by the French occupier in 1794 and by the German occupier in 1944, but could be brought back to Bruges again and again.Lanchals Chapel

Pieter Lanchals (1440-1488) was the Bruges bailiff who was beheaded by the people of Bruges for his loyalty to Burgundy and to Maximilian of Austria. His head was exhibited at the Gentpoort . His grave monument was partly preserved in the Church of Our Lady.

According to a legend that dates back to the 19th century, Emperor Maximilian I , husband of Mary of Burgundy , set the city to maintain 52 long-necked or swans and swim in the canals on the eternal day .

Arriving at the Market place, the first building catching your eye is the Belfry.

The Belfry formerly housed a treasury and the municipal archives, and served as an observation post for spotting fires and other danger. A narrow, steep staircase of 366 steps leads to the top of the 83 m (272 feet) high building, which leans 87 centimeters to the east.

To the sides and back of the tower stands the former market hall, a rectangular building only 44 m broad but 84 m deep, with an inner courtyard. The belfry, accordingly, is also known as the Halletoren (tower of the halls).

Belfry of Bruges

Belfry of Bruges Front gate of the belfry

Front gate of the belfry Market place, The white building is the Provincial Court

Market place, The white building is the Provincial Court Most other buildings surrounding the Market are commercial

Most other buildings surrounding the Market are commercial Entrance gate of the Belfry

Entrance gate of the Belfry Walking under the tower to the courtyard

Walking under the tower to the courtyard Staircase to the tower

Staircase to the towerBelfry history

The belfry was added to the market square around 1240, when Bruges was an important centre of the Flemish cloth industry. After a devastating fire in 1280, the tower was largely rebuilt. The city archives, however, were forever lost to the flames.

The octagonal upper stage of the belfry was added between 1483 and 1487, and capped with a wooden spire bearing an image of Saint Michael, banner in hand and dragon underfoot. The spire did not last long: a lightning strike in 1493 reduced it to ashes, and destroyed the bells as well. A wooden spire crowned the summit again for some two-and-a-half centuries, before it, too, fell victim to flames in 1741. The spire was never replaced again, thus making the current height of the building somewhat lower than in the past; but an openwork stone parapet in Gothic Revival style was added to the rooftop in 1822.

A poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, titled "The Belfry of Bruges," refers to the building's checkered history: In the market-place of Bruges stands the belfry old and brown; Thrice consumed and thrice rebuilded, still it watches o'er the town. Bells The bells in the tower regulated the lives of the city dwellers, announcing the time, fire alarms, work hours, and a variety of social, political, and religious events. Eventually a mechanism ensured the regular sounding of certain bells, for example indicating the hour.

In the 16th century the tower received a carillon, allowing the bells to be played by means of a hand keyboard. Starting from 1604, the annual accounts record the employment of a carilloneur to play songs during Sundays, holidays and market days.

In 1675 the carillon comprised 35 bells, designed by Melchior de Haze of Antwerp. After the fire of 1741 this was replaced by a set of bells cast by Joris Dumery, 26 of which are still in use. There were 48 bells at the end of the 19th century, but today the bells number 47, together weighing about 27.5 tonnes. The bells range in weight from two pounds to 11,000 pounds.

The town hall of Bruges is one of the oldest in the Low Countries and stood example for several town halls that were erected in other towns afterwards. Next stop is Town Hall on the Burg square

The Bruges town hall was built in 1376, which makes it one of the oldest town halls in the Low Countries. The city has been ruled from here for over 600 years. The gothic hall is a work of art in itself, with splendid 19th century murals and a colourful vaulted ceiling. The painted figures depict Bruges’ glorious past. The theme "citizens and government" sheds light on the eternal power struggle between the city government, the sovereigns, and the people of Bruges.

Following the murder of Charles the Good in 1127, Bruges received a city charter, leading to further political autonomy and designating its own council. In 1376, the building of a town hall on Burg Square began. Its construction lasted for centuries, partly due to problems related to a lack of space. At the end of the 19th century, city architect Delacenserie performed a radical 20-year renovation, (the new Gothic Hall). During a restoration of the façade in 1959, the statues were deemed to be of poor quality and were removed. The argument in Bruges over how to fill the empty alcoves lasted until 1989. Eventually the city requested sculptors to reinstate the original statues of rulers and biblical figures.

Facade details

Facade details Town hall Museum

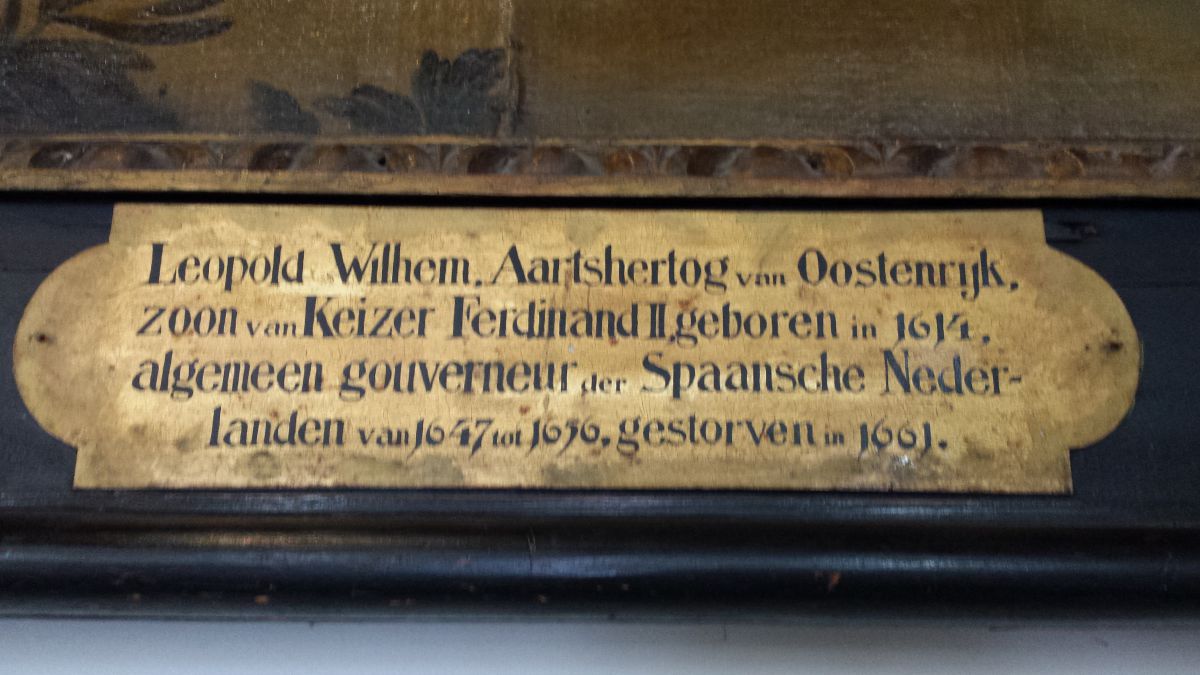

Town hall Museum Label on below next painting of Leopold Wilhem {fa-hand-o-right fa-lg }

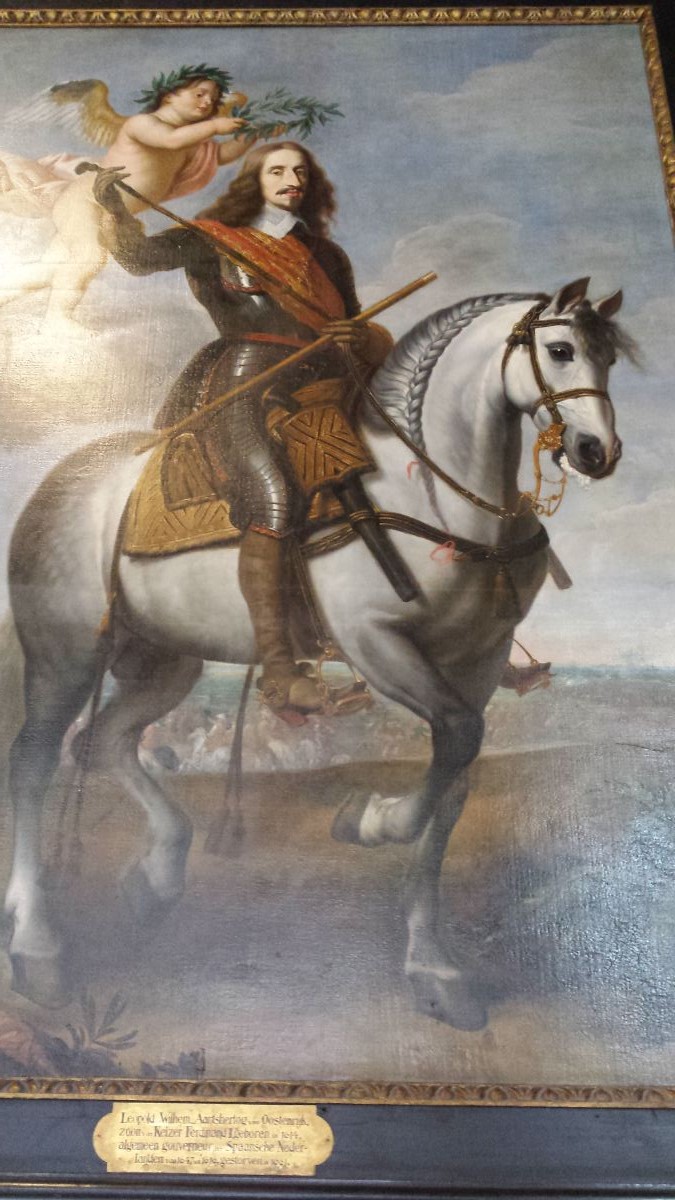

Label on below next painting of Leopold Wilhem {fa-hand-o-right fa-lg } Equestrian Portrait of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm

c. 1650 painted by Jan van den HOECKE

Equestrian Portrait of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm

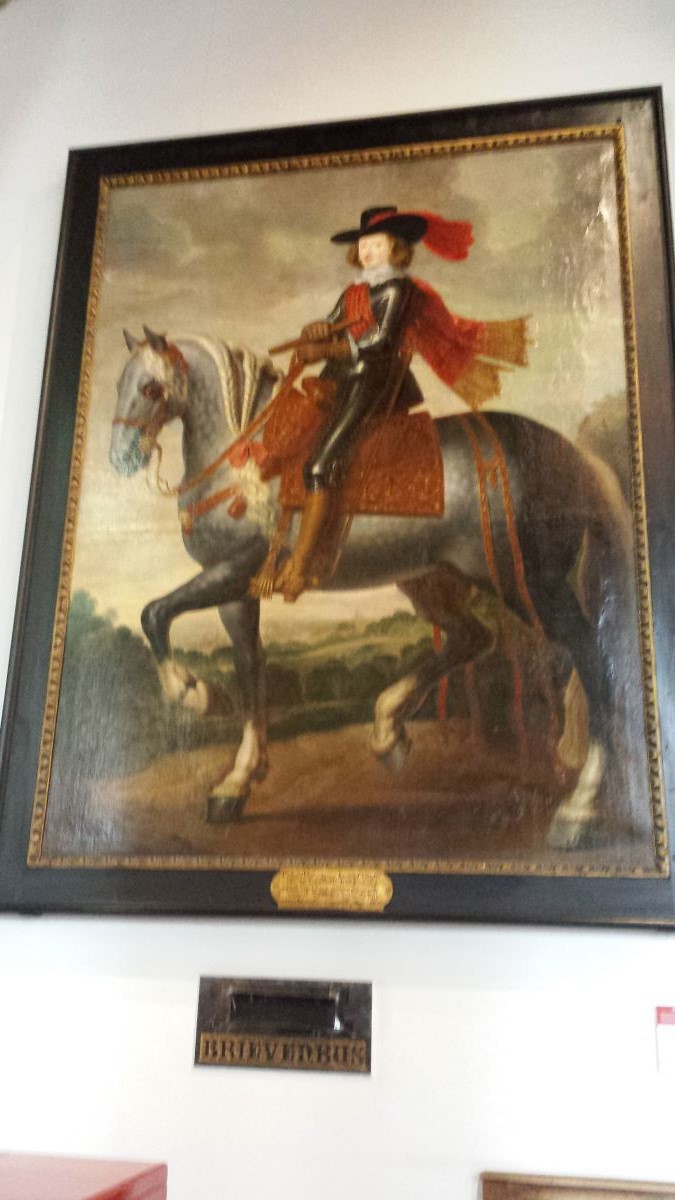

c. 1650 painted by Jan van den HOECKE Leopold Wilhem Governor of the Spanish Netherlands

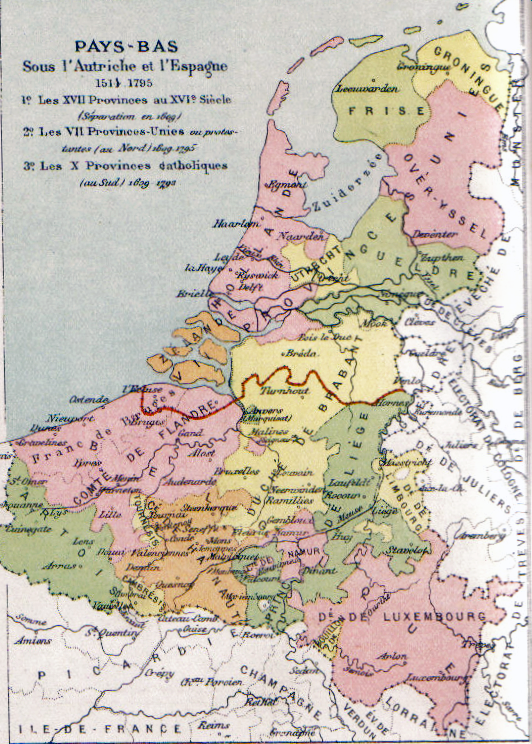

Leopold Wilhem Governor of the Spanish Netherlands The Spanish Netherlands or "lage landen"

The Spanish Netherlands or "lage landen" Gotic hall middle

Gotic hall middle Tribute to those who revived Bruges, by Charles Rousseau, 1910.

Tribute to those who revived Bruges, by Charles Rousseau, 1910. The Battle of the Golden Spurs, the creation of the Order of the Golden Fleece, by Albrecht De Vriendt, late 19 century

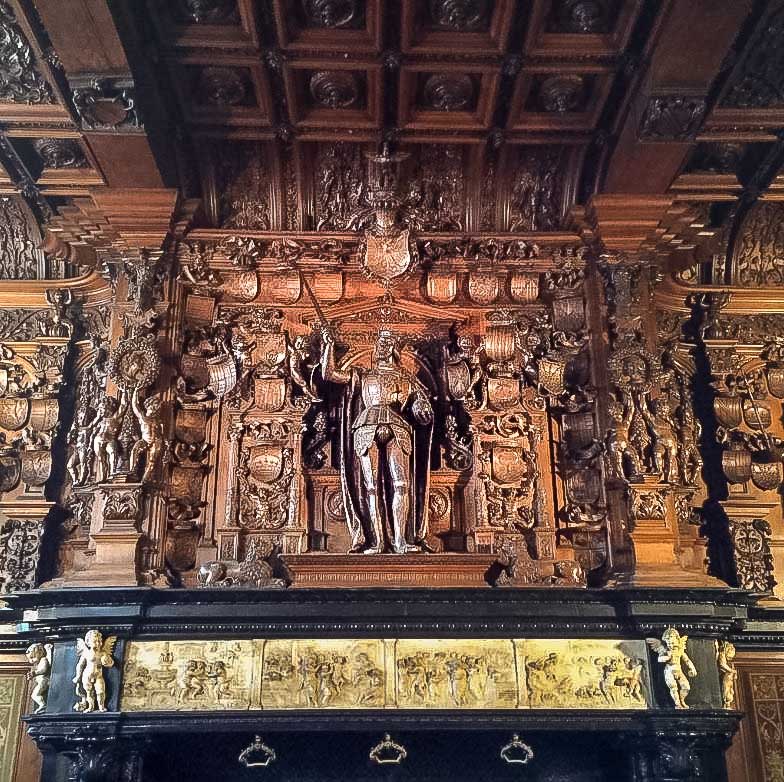

The Battle of the Golden Spurs, the creation of the Order of the Golden Fleece, by Albrecht De Vriendt, late 19 centuryPalace of the Liberty of Bruges or "De Brugse Vrije", is next door of Town hall. The alderman’s hall reflects royal power and justice. The Liberty's council chamber, which has been restored to its original 16th-century condition. The hall has a superb black marble fireplace decorated with an alabaster frieze and topped by an oak chimneypiece carved with statues of Emperor Charles V and his grandparents: Emperor Maximilian of Austria, Duchess Mary of Burgundy, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, and Queen Isabella I of Castile. Dating from 1528 and designed by Lanceloot Blondeel, the fireplace of oak, marble, and alabaster is one of the most important works of Renaissance art in Bruges.

Palace of the Liberty Facade

Palace of the Liberty Facade Palace of the Liberty Facade golden details

Palace of the Liberty Facade golden details Fireplace topped by an oak chimneypiece carved with statues of Emperor Charles V and his grandparents

Fireplace topped by an oak chimneypiece carved with statues of Emperor Charles V and his grandparents black marble fireplace with an alabaster frieze

black marble fireplace with an alabaster frieze Close up of the sculptures on the corner of the mantle

Close up of the sculptures on the corner of the mantle Close up of the sculptures on the corner of the mantle

Close up of the sculptures on the corner of the mantle Bust of Charles V

Bust of Charles V

Meeting of Council of the Brugse Vrije at the Manor of the Brugse Vrije (painter Gilles van Tillborch, early 17th century)

Meeting of Council of the Brugse Vrije at the Manor of the Brugse Vrije (painter Gilles van Tillborch, early 17th century) The 16th century rear facade of the manor on the 'Groenerei'.

The 16th century rear facade of the manor on the 'Groenerei'. The 'Burg', painted c. 1691-1700 by Jan Baptist van Meunincxhove

The 'Burg', painted c. 1691-1700 by Jan Baptist van MeunincxhoveGroeninge Museum The Fine Arts Museum of Bruges, better known as the Groeningemuseum, is internationally renowned for its significant holdings of early Netherlandish painting, which has formed the core of the museum’s most successful exhibitions in recent decades. This part of the collection consists of a number of masterpieces by Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, Hugo van der Goes and Gerard David, as well as works by the minor masters active in Bruges in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, including the Masters of the Lucia- and Ursula Legend, Ambrosius Benson, Lancelot Blondeel and Pieter Pourbus the Elder. The paintings deribed below are described by Web galelery of Arts

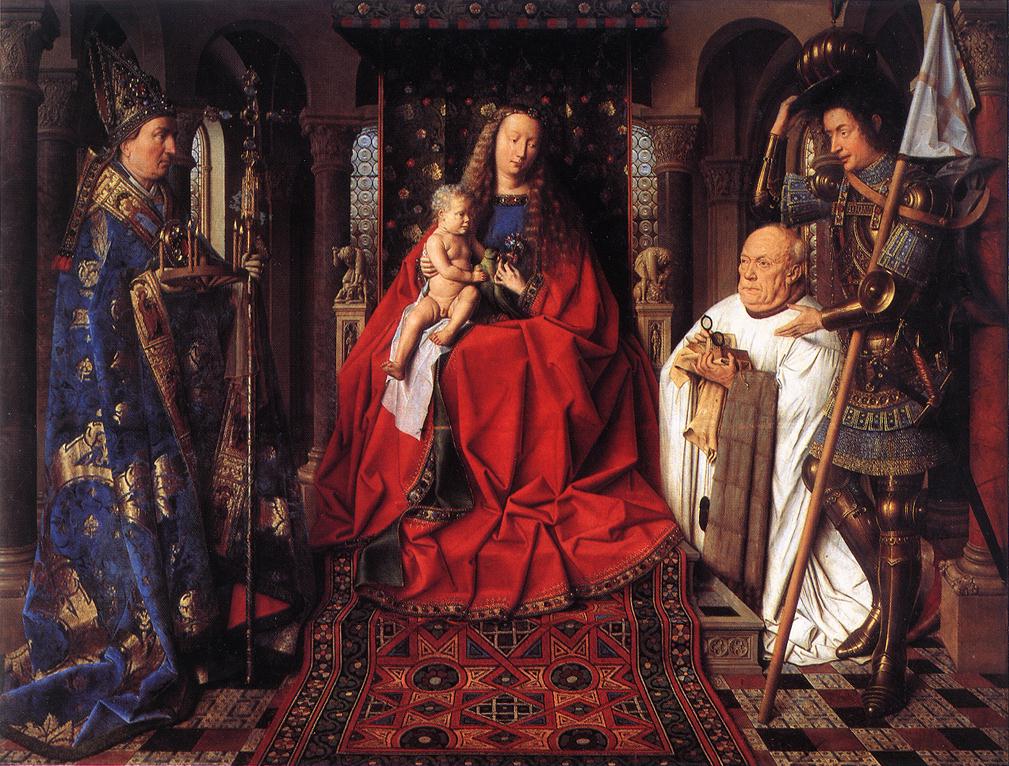

The Madonna with Canon van der Paele.

The Madonna with Canon van der Paele.Painted circa 1436 by Jan Van Eyck

This is how van der Paele might have expressed the message of the painting-that paradise was at hand-a message confirmed by its being set in a very real but also sacred context. The Virgin is pictures holding a nosegay and her son a parrot - unmistakable echoes of the Garden of Eden - and both figures have turned to face the meditating canon.

The painter uses the apostles to ring the changes on the different varieties of grief, and their profound sadness contrasts with the detachment of the Virgin herself. Their clothes have been creased into countless shifting folds which cut across one another at right angles. Van der Goes is revealed as a penetrating analyst of religious feeling, of grief and devotion, and of the agitation they can cause. This work, like all those he painted during his last period, represents the eruption of sacred experience into a profane world. The artist achieves this through an abundant use of colours which strike the viewer as unreal, as if they were themselves transfigured. In this way, Van der Goes seeks to identify his painting with the mystery of transcendence itself.

To this end too, the gestures of his figures are emphatic. He uses techniques or the progressive reduction of pictorial space and the transformation of figures, which he paints half-length, not full length.

The Death of the Virgin.

The Death of the Virgin.Painted circa 1478 and 1482 by Hugo van der Goes

Retable of Saint Nicholas

Retable of Saint NicholasDonated as a Van Eyck, the central panel was very soon ascribed to the Master of the Legend of St Lucy. As with another series of panels by this master, as well as by his contemporary and fellow-citizen the Master of the Legend of St Ursula, a date has been suggested on the basis of the stage of building of the carefully portrayed Bruges belfry. Seeing that the octagonal crown with the wooden steeple was built between 1482 and 1486 and, after the fire of 1493, rebuilt from 1499 to 1502, a painting in which the belfry has this superstructure could have been made between 1486 and 1493 or after 1502. The former dating seems to be more probable.

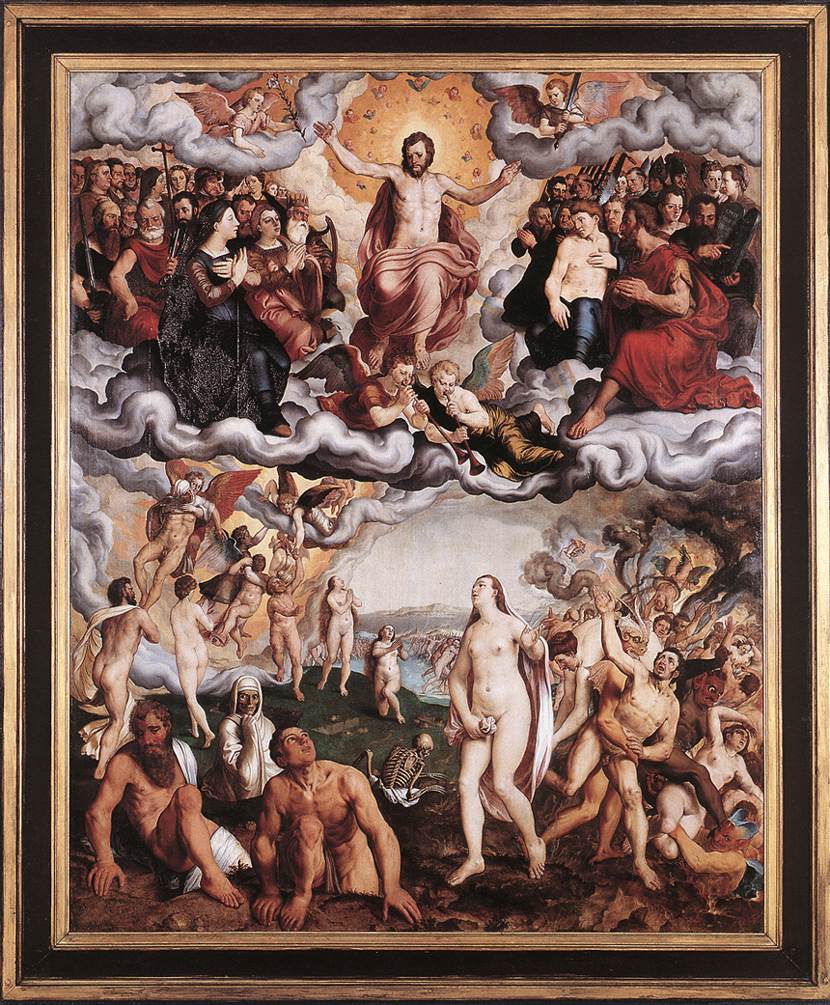

Last Judgment. Painted circa 1551 by Pieter Pourbus

Last Judgment. Painted circa 1551 by Pieter PourbusAfter a late lunch, we stroll around the city, until late afternoon. The temperature drops and we start walking in the direction of the train station.

Wollestraat. Here you can take a boat ride on the canals

Wollestraat. Here you can take a boat ride on the canals Walk to the Arendshuis museum

Walk to the Arendshuis museum Bonifacius bridge. Back side of church of Our lady

Bonifacius bridge. Back side of church of Our lady Park bridge part of Minnewaterpark

Park bridge part of Minnewaterpark Park bridge with the Powder Tower in the back

Park bridge with the Powder Tower in the back

Comments powered by CComment